Continental Divide Trail Gear List and Strategy

THIS CDT GEAR STRATEGY IS BASED ON 13,000 CdT MILES OF TRIAL AND ERROR

Home > Trip Guides > Thru Hikes

Updated January 16th, 2025

Many thru-hikers consider the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail (CDT) the most challenging of the Triple Crown Trails (Continental Divide Trail, Pacific Crest Trail, and Appalachian Trail). The CDT spans 5 states over roughly 2,900 miles from Mexico to Canada—going through 21 wilderness areas, 3 national parks, and 25 national forests. This article explains the logistics, planning, itinerary, gear list, permits, and tips and advice for northbound and southbound thru-hikers and section-hikers.

We’ve thru-hiked the Continental Divide Trail 4 times. Liz Thomas, one of our writers, is a former employee of the Continental Divide Trail Coalition, the non-profit partner to the US Forest Service on the CDT. She also wrote the book Best Day Hikes on the CDT: Colorado and Long Trails: Mastering the Art of the Thru-hike.

Our goal is to prepare you for the CDT’s challenging terrain so you can have a safer and more enjoyable trip. The CDT is worth the efforts — the CDT rewards the hiker with world-class scenery and an authentic wilderness experience.

A CDT thru hike usually takes 4 to 5 months, and thru-hikers must prepare for varying weather conditions. Whether you're looking for an ultralight gear strategy or a traditional kit, we have a wide range of recommendations across the gear spectrum.

Continental Divide Trail Quick Facts

Mike Unger (left) has thru-hiked the CDT twice in addition to also re-hiking (for a third time) sections of the CDT in New Mexico and Colorado. Naomi Hudetz (right) is an editor at Treeline Review and has thru-hiked more than a dozen long distance trails, including the CDT.

Distance: Varies based on routes chosen, but generally around 2,980 miles (4,800 km)

Time to hike the entire trail: 4-5 months

Elevation gain: 470,000' (143,000 meters)

Elevation loss: 470,000' (143,000 meters)

High Point: Grays Peak Summit (14,254' or 4,344 meters)

Low Point: Lordsburg, NM (4,189 feet or 1,277 meters)

Best season: May to October (depending on the direction hiked)

Permits: Required in certain sections; see our permit section below

Difficulty: Strenuous

The CDT goes through all or part of New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana; these are the ancestral lands of the Chiricahua, Apache, Western Apache, Zuni, Pueblo, Diné (Navajo), Ute, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Eastern Shoshone, Shoshone-Bannock, Lemhi Shoshone, Apsaalooke, Niitsitapi, Salish Kootenai, Ktunaxa, and Tsuu T’ina peoples.

We create reader-supported, objective, independently-selected gear reviews. This story may contain affiliate links, which help fund our website. When you click on the links to purchase gear, we may get a commission — without costing you an extra cent. Thank you for supporting our work and mission of outdoor coverage for every body! Learn more.

A CDT thru-hiker’s complete backpacking kit drying at a trailhead.

CDT Gear List

The CDT is a difficult trail, even for experienced thru-hikers, and having lightweight gear that provides some margin of safety and comfort is worth it. This CDT gear list has a base weight of 13 pounds.

This lightweight CDT gear list is highly recommended for first-time thru-hikers because the items are intuitive and time-tested on the CDT. The less mental energy spent on gear, the more mental energy you have to develop a self-care routine and strategies to thrive and complete your goal.

| GEAR | MODEL | WEIGHT (ounces) | WEIGHT (ounces) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pack, Shelter, Sleeping | Women | Men | |

| Backpack | Six Moon Designs Swift X Hiking Backpack (vest harness) | 40.20 | 40.20 |

| Waterproof Pack Liner | Six Moon Designs Pack Liner (50L) | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Shelter | Zpacks Plex Solo Classic Tent | 15.48 | 15.48 |

| Tent Stakes | MSR Ground Hog Stakes x 10 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Stake Sack | Zpacks Stake Sack | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Sleeping Bag | Feathered Friends Egret UL 20 (Women's) Feathered Friends Swallow UL 20 (Men's) |

27.50 | 27.30 |

| Sleeping Pad | Therm-a-Rest NeoAir XLite NXT (regular) | 13.00 | 13.00 |

| Total Pack, Shelter, Sleeping (ounces) | 104.29 | 104.09 |

Northbound CDT hikers in the Southern San Juan section, which is often almost completely covered in snow for a hundred miles in May and early June.

CDT Ultralight Gear List

We recommend this CDT gear list for those with long-distance hiking experience who want to upgrade or tailor their gear list for a drier, western climate. This ultralight backpacking gear list has a base weight of less than 8 pounds. It requires some extra skills to manage and is best suited for those who hike quickly and can complete their hike during the season with the least-intense weather and conditions.

| GEAR | MODEL | WEIGHT (ounces) | WEIGHT (ounces) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pack, Shelter, Sleeping | Women | Men | |

| Backpack | Zpacks Nero Ultra 38LBackpack | 10.30 | 10.30 |

| Waterproof Pack Liner | Nyloflume Pack Liner | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Shelter/ Rain Gear | Six Moon Designs Gatewood Cape | 11.00 | 11.00 |

| Tent Stakes | Vargo Outdoors Titanium Shepherd's Hook Tent Stakes x 6 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

| Stake Sack | Zpacks Stake Sack | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Bivy | Mountain Laurel Designs SuperLight Solo Bivy (with DCF floor) | 5.50 | 5.50 |

| Ground Sheet | Mountain Laurel Designs DCF Ground Cloth (solo) | 1.75 | 1.75 |

| Sleeping Quilt | Katabatic Palisade 30F Quilt (900fp) | 17.80 | 18.90 |

| Sleeping Pad | Therm-a-Rest NeoAir XLite NXT (short) | 11.50 | 11.50 |

| Total Pack, Shelter, Sleeping (ounces) | 60.46 | 61.56 |

Treeline Review photographer in the Wind River Range, Wyoming on the CDT.

FAQ about the CDT

Where does the Continental Divide Trail start and end?

The CDT spans the entire length of the United States from Mexico to Canada. The official southern terminus is in the New Mexico bootheel, at the Crazy Cook Monument. There are two official northern termini — Waterton Lake and Chief Mountain. Southbound thru-hikers usually start at Chief Mountain due to the high snow at Waterton Lake in June. Northbound hikers usually finish at Waterton Lake.

Is the Continental Divide Trail finished?

Almost! The Continental Divide Trail Coalition (CDTC) reports that the CDT is "95% protected as public land", with a few gaps remaining in New Mexico, Colorado, and Montana. We love seeing the CDT evolve and mature into the magnificent trail it is today!

How challenging is the Continental Divide Trail?

Like any outdoor activity, the challenge will depend upon your skill set. The CDT is a challenge physically, mentally, logistically, and navigationally. Staying safe in snow, lightning, heat, and other weather is also more difficult on the CDT than on many other trails. But as with all thru-hikes, it's what you bring to it that matters.

Is the Continental Divide Trail dangerous?

There are dangers associated with most outdoor activities, and the CDT is no exception. Grizzly bears probably come to mind for most people. We encourage you not to let these perceived dangers deter you from hiking the CDT. You can mitigate these risks by being prepared, carrying proper gear, and honing your skills. Consider taking a Wilderness First Aid course and bring and know how to use a first aid kit.

Do I need a permit to hike the CDT?

There are several areas where permits are required. There is no single permit for the entire trail (like the Pacific Crest Trail). See our section on permits for more details.

How long is the Continental Divide Trail?

The CDT has many alternative route options (which is one of the many things we love about the CDT), so the mileage for every hiker will be slightly different. The CDTC's website says it is 3,059 miles, while the FarOut app shows 2,982 miles. Most Continental Divide Trail hikers would say their hike was between 2,700 and 2,900 miles.

How long does it take to thru-hike the Continental Divide Trail?

The time to take the CDT depends on many factors, but most hikers take 4 to 5 months to complete it. It will depend on your daily mileage, the alternates you take, the number of zero days (rest days), whether there are any fire closures, etc.

How much does it cost to hike the Continental Divide Trail?

There's a vast range here, but the current rule of thumb is that it will cost a minimum of $2 per mile to hike a long trail in the U.S., excluding gear. This estimate assumes a bare-bones experience. That means only a few nights in hotel rooms, limited restaurant meals, and using hiking gear you already have until it is threadbare. This estimate does not include off-trail expenses, such as a storage unit (if you move out of your home), health insurance, and cell phone.

When our editor Liz worked at the Continental Divide Trail Coalition, we would keep track of people who spent less than $5,000 on the trip because it represented less than half of hikers. That sounds like a lot, but remember this is a trip that is often 6 months and 2,800-miles long and works out to cost about $2 a mile.

We know hikers who put their entire hike on a credit card and paid it off later — and we positively, absolutely do not recommend this. Save up for your hike beforehand so that you don't worry about how you'll pay for it during the entire hike.

When is the best time to start the CDT?

If you're hiking northbound starting in New Mexico, the best time to start is mid-April to mid-May. If you're hiking southbound starting in Montana, the best time to start your thru-hike is mid-June to early July.

Continental Divide Trail Trip Planning Resources

Far Out

FarOut has a navigational app that, besides navigation, also provides comprehensive Gateway Community information. Lodging, restaurants, grocery stores, post office, laundromats, fuel, gear stores, medical facilities, trail registers, and libraries are all listed. In addition, hikers add comments with other good information (such as who has the best sandwiches).

Guidebooks

The Continental Divide Trail Coalition (CDTC) has an excellent trip planning guide. There is a suggested donation of $10.

Jackie "Yogi" McDonnell has published and updated her CDT Handbook and laminated resupply list for nearly 20 years. [Note: Yogi hasn't updated her handbook since 2019, and it isn't clear when or if she will update it again.]

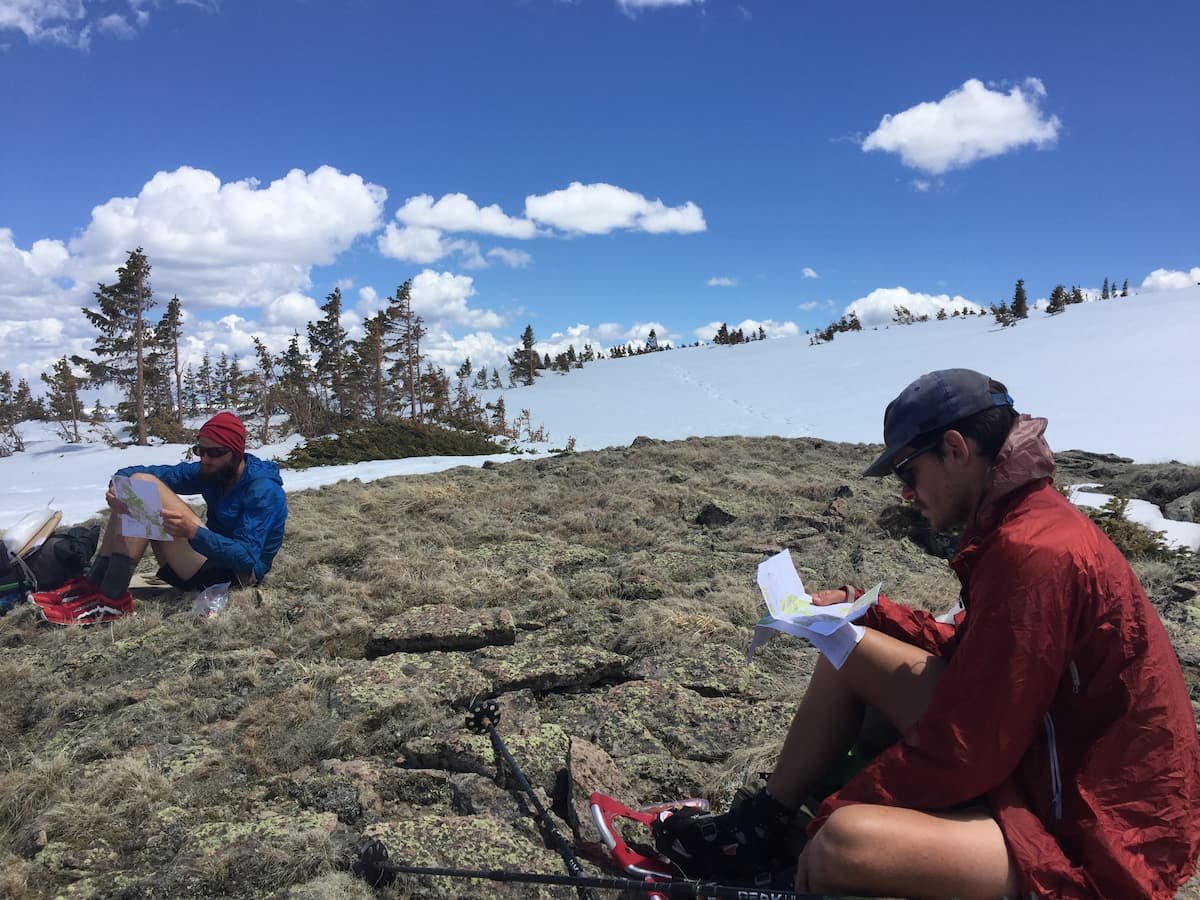

CDT hikers looking at maps in Colorado.

Paper Maps

CDTC Maps

The CDTC has an excellent map set with topographic information, elevation charts, water sources, and waypoints. The maps are also available for offline use in the Avenza Maps app.

Bear Creek Survey Maps

Bear Creek Survey sells spiral-bound printed map books — one for each state, plus a book with all of the alternates. You can also download them digitally and print the maps yourself.

Jonathan Ley Maps

Before there were good data sources, Jonathan Ley produced his own maps to use on his 2001 CDT thru-hike. Since then, he has updated the maps every year with comments from the previous years' hikers and made them available to everyone. Affectionately known as J-Ley maps to thru-hikers, the maps and annotations have been invaluable for thousands of hikers. You can also load them into the Avenza Maps app for offline use on your phone. [Note: the maps have not been updated since 2020, and it isn't clear when or if Jonathan will update them again.]

National Geographic Maps

If you want commercially available marketed maps, Nat Geo has detailed topo maps of the National Parks, Wind River Range, and most of Colorado. Using these overview maps may help you design bail-out options in cases of high snow, wildfire, or alternate routes you may want to take.

A CDT marker and cairn in New Mexico. While the CDT was once infamous for its lack of navigational markers, in recent years, it has become much easier to navigate, especially with navigational apps and handheld GPS. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Navigational Apps

FarOut

The FarOut CDT app is handy and has almost all of the information you'll need during your hike. It's available offline, as long as you download the maps before leaving. Since the maps take up so much space, we recommend downloading them in sections during your hike. Just be sure that you'll be in a place with decent WiFi before you run out of maps!

Gaia GPS

The Gaia GPS app is a pure navigation app that can be used even when you don't have cell phone coverage (as long as you download the maps on your phone before leaving). You'll also need to download the GPX tracks for the trail to your phone, available from the CDTC.

Gaia has a vast range of data layers available in addition to topographic maps, although some are available in the premium version only. Some of our favorite map layers include:

Cell coverage (T-Mobile, US Cellular, Verizon, AT&T)

Private land overlay

Public land overlay

NatGeo Trails Illustrated

Native Land Territories

Shaded relief

USFS Roads and Trails

Wildfires (current)

Light pollution

Precipitation forecast

Snow forecast

We've found the Verizon cell coverage layer to be surprisingly accurate.

Avenza

The Avenza Maps app is a digital map store that can be used on your phone, even when you don't have cell phone coverage. There are two sets of CDT maps available for Avenza — both of which are free, but a $10 donation is recommended for the CDTC:

The official maps from the CDTC

The crowdsourced maps from Jonathan Ley

Water Reports

Water is limited in certain sections of the CDT, and having up-to-date information is crucial.

FarOut App

The FarOut app lists water sources and the distance from the current source to the next source. Hikers regularly update the app with information about the quantity and quality of water available, so we highly recommend hikers use the FarOut app for the water information alone.

Pro tip: always update the FarOut app with the latest comments when you get to town or have cell coverage, as water information changes quickly in the desert. We also recommend downloading the USGS base maps in addition to the Google Map layers that come with the app. This becomes very useful when trying to understand topography and escape routes.

CDTC Water Report

The CDTC also maintains a water report. This report is crowdsourced, so if you use this, we highly recommend that you contribute your comments to keep hikers behind you up-to-date.

Trail Conditions

The CDTC published information about trail closures and restrictions here. For current wildfires and closures due to wildfires, check Inciweb.

The Gaia GPS App has a wildfire overlay.

A CDT thru-hiker among wildflowers in the Wind River Range, Wyoming. Photo by John Carr.

Should I hike the CDT Northbound or Southbound?

This question has no easy answers! Many hikers have opinions about this (shocking, we know), but ultimately, you'll need to weigh the pros and cons about what works for you, other obligations in your life, and your schedule.

We'll also throw another idea into the mix: a flip-flop hike. Flip-flopping means you start somewhere in the middle of the trail and hike north/south to the terminus. Then, you return to your starting point, hike south/north, and finish at the other terminus. Flip-flopping is very common on the CDT. Many thru-hikers avoid the snowy San Juan Mountains of Colorado in May or June by flipping to the dry Great Basin of Wyoming.

So below, we put together a list of pros and cons for each option. Take time to think about this, read trail journals (at least one in each category), and talk to thru-hikers in person if possible.

Treeline Review photographer John Carr at the southern terminus of the CDT. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Getting to and from the Southern Terminus of the CDT

The southern terminus of the CDT, the Crazy Cook Monument, is not easy to reach. The closest town with transportation, lodging, and restaurants is Lordsburg, NM. Getting to Lordsburg is usually done with planes, trains, automobiles, or some combination of the three. And from Lordsburg, the monument is 3 hours away on some pretty terrifying roads (luckily, there's a shuttle for that part).

Getting to Lordsburg, New Mexico

Flights

The closest airports to Lordsburg are El Paso, TX (ELP) (2.5 hours), Tucson, AZ (TUS) (2.5 hours), and Albuquerque, NM (ABQ) (4.5 hours). You'll need to catch a Greyhound bus or Amtrak train from the airport.

Greyhound

Greyhound stops in Lordsburg, with service to all three airports mentioned above. It's a three-hour trip from El Paso, a 7.5-hour ride from Albuquerque, and 1.5 to 3 hours from Tucson (depending on the bus — a non-stop option is available from Tucson).

Amtrak

Amtrak serves Lordsburg via its Sunset Limited line, which runs from Los Angeles to New Orleans. You can catch the Amtrak train in Tucson and El Paso metro areas. The Sunset Limited only operates three days per week, so plan your connecting flights accordingly!

The Crazy Cook southern terminus monument for the CDT is a remote part of southern New Mexico. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Getting from Lordsburg to Crazy Cook

Once you make it to Lordsburg, it's still a three-hour drive (on roads impassible by standard passenger cars) to the Mexican border and the Crazy Cook Monument (the southern terminus of the CDT). Luckily, there are two shuttle options just for thru-hikers.

CDTC Shuttle to Crazy Cook

The CDTC has made it easy and offers a shuttle service from Lordsburg to the border from April through mid-May. As part of the shuttle service, the CDTC also caches water at 5 places along the route to Lordsburg (2 gallons per cache). These water caches are crucial in this first section of the CDT. Reserve your trip early, as spots are limited. The shuttle runs on a fixed schedule in the spring.

If you're southbounding and need to get from Crazy Cook to Lordsburg in the fall, the CDTC shuttle is on demand and subject to driver availability. When you're close to finishing and know when you'll be at the border, you should contact the CDTC to set up your shuttle.

Camp Crazy Cook Shuttle

Two former CDT thru-hikers run the Camp Crazy Cook Shuttle. They'll pick you up at the McDonald's in Lordsburg and drop you off at the Mexican border. They’ll stop at the store in Hachita for fuel canisters, coffee, and snacks.

Getting to and from the Northern Terminus of the CDT

Treeline Review co-founders Liz Thomas and Naomi Hudetz are standing at Waterton Lakes at the US-Canadian border is the northern terminus of the Continental Divide Trail.

There are two official northern termini of the CDT: Chief Mountain and Waterton Lake. Most southbound hikers start at Chief Mountain, and most northbound hikers finish at Waterton Lake.

Waterton Lake Terminus

The Waterton Lake Terminus is an official port of entry on the United States and Canada border. There are no roads here, so you must continue hiking 3.9 miles into Canada along Waterton Lake to the Waterton townsite. Waterton is within Waterton National Park, and it has decent restaurants, lodging, camping, and grocery options.

If you cross the US/Canadian border, you must notify Canadian Customs. The procedure for crossing the border may change at any time, so please do your homework before entering Canada. As of 2023, you must notify Canadian customs of your arrival at (403) 653-3535 after arriving at the Waterton townsite. You must have your US Passport or US Passport Card. Hikers from other countries may have other requirements.

A mountain goat in Glacier National Park as spotted by a southbound thru-hiker.

If you're planning on starting your southbound hike at the Water Lake Terminus, you must report your entry from Canada into the US to Customs and Border Protection (CBP) through their app CBP ROAM. A video chat through the app may be required. Since there is limited cell service along Waterton Lake, you can complete this up to 5 hours before entering the U.S. There are also iPads available for public use at two kiosk locations if you don't want to use your phone. Read more about the CBP ROAM app here.

Unfortunately, there are no easy ways to get to or from the Waterton townsite. Airport Shuttle Express travels between the Calgary airport (YYC) and Waterton (and Kalispell, East Glacier, and West Glacier). However, it is a charter service and extremely expensive. Many hikers have decent luck with hitchhiking.

The closest airports to Waterton are Calgary, AB (3 hours) and Kalispell, MT (4 hours + border crossing time).

Chief Mountain Terminus

Most southbound hikers begin at the Chief Mountain terminus to avoid the technically difficult snow cornices of the Ahern Drift and Swiftcurrent Pass. Some northbound hikers also finish at Chief Mountain if they don't have a passport or aren't allowed into Canada. You do not need a passport because you won't be leaving the U.S.

Getting to and from Chief Mountain is challenging.

Flights

The closest U.S. airports to Chief Mountain are Kalispell, MT (FCA) (2 hours) and Missoula, MT (MSO) (3.5 hours). The Calgary airport is a 4-hour drive, with extra time needed for the border crossing. You might be able to get to the Kalispell airport via a private shuttle service, such as:

Arrow Shuttle

Mountain Shuttle

Amtrak

Amtrak's Empire Builder train stops in East Glacier, MT. The Empire Builder line stops in many major cities, including Chicago, St. Paul/Minneapolis, Fargo, Spokane, Sandpoint, White Salmon, Portland, and Seattle. It connects to most other Amtrak lines in Chicago and the Coast Starlight train in Portland and Seattle.

Getting from East Glacier to Chief Mountain

Once you're in East Glacier, you can hop a shuttle from Glacier Park Lodge to Two Medicine or St. Mary Village. From St. Mary, you'll likely need to hitchhike to Chief Mountain. Chief Mountain is also the terminus of the Pacific Northwest Trail.

The Indian Peaks wilderness is one of the few national forest areas along the Continental Divide Trail that requires hikers to have a permit for camping. Photo by John Carr.

Permits Required for the CDT

Unlike the Pacific Crest Trail, there isn't a single permit covering the entire CDT. However, there are certain areas where a permit is required.

Glacier National Park

Glacier National Park requires both northbound and southbound hikers to have backcountry permits for designated backcountry campsites. Campsites are 70% reservable and 30% walk-up. Distance is limited to 16 miles per day for advance reservation permits; higher mileage is allowed only on walk-up permits.

For the past couple of seasons, the NPS has utilized a lottery system:

For groups of 1-8 people, the lottery is open for the 24 period on March 15th, from 12:00 am (MT) to 11:59 pm (MT)

There is a $10 lottery fee (non-refundable)

There are 3,000 lottery “winners” chosen at random (there’s no advantage to being the first person to submit an application)

Winners are notified on March 17th

Winners are not guaranteed their desired itinerary; it only gives you early access to make a reservation

Winners can reserve their desired itinerary from March 21st through April 30th on recreation.gov

Winners are randomly assigned into smaller groups with an early access date and time window to make a reservation

If your reservation is successful, additional fees apply

You must have a recreation.gov account to register for the lottery

You must pick up your permit in person at a wilderness permit issuing station the day before or the day of your itinerary start date by 4:30 pm, or it will be canceled

All campsites not issued during the early access lottery period will be released to the general public on May 1st

Reservations are available for trips beginning June 15th through September 30th

Wilderness campsites can hold 2 tents and 4 people

It can be difficult to get to a wilderness permit issuing station if you don’t have a car in Glacier. Some hikers rent a car in East Glacier to drive to a permit station. There’s also the $25 East Side Shuttle that runs several times a day (June through September) from East Glacier Lodge to Two Medicine, where you can obtain your permit.

Note that last year, permits were not available at the Two Medicine Ranger Station (which is open from May 26 through September 30). If they do that again this year, the nearest Wilderness Permit issuing station to Two Medicine is the St. Mary Visitor Center. Check here for updates. Either way, once you pick up your permits, the shuttle can take you back to East Glacier.

Walk-up permits are available the day before or the day of your trip start date.

Glacier National Park is one of the places on the CDT that requires thru-hikers get a permit.

We strongly encourage southbound hikers to get an advance permit.

Northbound hikers will be finishing their hikes in Glacier, so knowing the dates you'll be in Glacier are extremely difficult to predict. Most thru-hikers do not have a problem getting a walk-up permit. However, in 2022 the Park Service changed the reservation/walk-up ratio from 50/50 to 70/30, making it more difficult for thru-hikers to get walk-up permits.

Blackfeet Reservation

The CDT passes through the Blackfeet Reservation on the south side of Glacier National Park, and a permit is required. You can get your permit online here.

Yellowstone National Park

Permits are required year-round to camp in the backcountry of Yellowstone National Park and can be obtained during the early access lottery on recreation.gov for reservations during the peak season (May 15 to October 31):

The early access lottery opens at 8 am MT on March 1st

The early access lottery closes at 11:59 pm MT on March 20th

Lottery winners will be notified on March 25th

Winners are given an early access window date and time between April 1st and 25th

Your itinerary is not required to register for the lottery

Lottery winners are not guaranteed their itinerary

Success of obtaining your ideal itinerary depend on the time of your early access window

Remaining reservations are released to the general public on April 26th

A portion of permits are held for walk-ups, which can be made up to 2 days in advance

Both northbound and southbound hikers will have a general idea of when they'll be in Yellowstone, but the exact dates are hard to predict. Therefore, the CDTC recommends calling YNP at 307-344-2160 when you have specific dates for your hike. I called beforehand on my CDT thru-hike, and I found the Yellowstone rangers incredibly helpful. They went out of their way to ensure that I got a permit that worked for me.

Rocky Mountain National Park

A backcountry permit for overnight camping is required for 25 miles of trail in Rocky Mountain National Park. A hard-sided bear canister is also required for overnight camping. Most thru-hikers avoid the permit and bear canister requirements by hiking through this section in one day. Of those 25 miles, part of the CDT forms almost a complete loop in RMNP. Most thru-hikers decide to cut off the loop portion to or from the town of Grand Lake — minimizing the number of miles in the park. If you'd rather camp in RMNP, you can read about the requirements here and reserve your permit here. Permits for May 1st to October 31st are released on March 1st.

Indian Peaks Wilderness

The CDT enters the Indian Peaks Wilderness three times. A permit for overnight camping is required from June 1st through September 15th. Most thru-hikers camp outside the wilderness to avoid the permit process. You can read more about the process here and get your permit here.

New Mexico State Trust Lands

Before 2023, a recreational permit was required for anyone recreating on New Mexico State Trust Lands. However, a recent agreement between the Bureau of Land Management and the New Mexico State Land Office removes the need for CDT hikers to obtain an extra permit to access the CDT.

CDT thru-hikers in the Gila River canyon in New Mexico, a popular alternate route. Photo by John Carr.

New Mexico

Distance: 777 miles (1,251 kilometers)

Elevation Gain: 89,000' (27,000 meters)

Elevation Loss: 83,000' (25,000 meters)

Low Point: Lordsburg (4,189 feet or 1,277 meters)

High Point: Mt. Taylor (11,301 feet or 3,445 meters)

New Mexico offers incredible sunsets, red rocks, and views you won't find anywhere else on the CDT. One advantage it has over other states is that it has less elevation gain and more predictable weather.

There will be days with very little shade, the potential for snow and postholing, multiple 20+ mile water carries, and blisters.

Even experienced hikers have reported pain and blisters in New Mexico. While there is less dirt road walking in New Mexico than in the past, some hikers find this challenging.

Culturally, many thru-hikers enjoy the towns in New Mexico, which have a history and demographic composition that give it a unique feel compared to other CDT states. Many hikers find the food excellent in trail towns due to the abundance of world-famous cuisine made of New Mexico hatch chiles. New Mexico may be the state with the most trail angels — locals who will help you along the way, whether by giving you water, meals, or even a place to stay the night indoors.

The first 100 miles of the CDT are cross-country with CDT signs within eyesight. Photo by John Carr.

Northbound

For northbound hikers, the start of the CDT can be overwhelming, even for seasoned long-distance hikers. Many thru-hikers told the CDTC that they found the first trail-less 100 miles the most challenging part of the Triple Crown Trails. If you're starting in New Mexico, we recommend acclimating for several days to the dry, high-altitude climate of southern New Mexico before starting.

Compared to other trails, the distances between towns in New Mexico can make for a rough start of a thru-hike. The first 100 miles northbound have no natural flowing water and almost no shade, so you'll rely on water caches placed in metal boxes. Many hikers will want to quit within the first 100 miles. You are not alone. It gets better, especially as you enter the higher altitudes in the Gila Wilderness. Regardless, try your best never to quit on a bad day!

One of many golden aspen-surrounded camps for Liz Thomas during her southbound CDT thru-hike.

Southbound

For southbound thru-hikers, the golden aspen, red rocks, and gentler terrain of New Mexico will be a welcome finish for the trail. However, it's easy to forget that New Mexico can be cold and snowy after making it so far. The northern section of New Mexico is still at a high elevation, and snow too deep to navigate has stopped and even killed one thru-hiker. If you were not already planning on carrying a satellite messenger on your thru-hike, be sure to carry one with you through northern New Mexico.

It is crucial that thru-hikers not underestimate New Mexico's challenges.

New Mexico will likely be cold for most southbound hikers, and it can be long distances between water. Many sources are dry by the fall.

This is a time to pick up a sleeping bag liner or warmer sleeping bag. See our gear review of the Best Ultralight Sleeping Bags for more recommendations.

As with Colorado and Wyoming, southbound hikers should be aware of local hunting dates and should consider wearing hunter orange hats, shirts, and other apparel for their safety. Hunters are generally friendly and only seen on roads (as most opt to stick to their vehicles) and have been known to trail magic (i.e., serve up a campfire-side feast) for thru-hikers.

Special Gear for New Mexico

Special Gear for Southbounders in New Mexico

Hunter orange hats and clothing

Extra insulating layers like a down jacket or synthetic jacket

Consider adding base layers if you don’t already have them

Colorado

A CDT hiker in Colorado among wildflowers. Photo by John Carr.

Distance: 726 miles (1,166 kilometers)

Elevation Gain: 145,000' (44,000 meters)

Elevation Loss: 146,000' (44,000 meters)

High Point: Gray's Peak (14,278 feet or 4,351 meters)

Low Point: Elk River (8,044 feet or 2,451 meters)

Colorado is home to the highest elevations on the CDT, including the trail's high point on Greys-Torreys Peaks — over 14,000 feet high. Colorado has beautiful vistas and fun and amenity-filled trail towns. But the Colorado CDT also has many challenges.

CDT hikers in the snow in the San Juan mountains of Colorado. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Even if the snowpack has melted out, it can rain or snow in any month in Colorado's high country, so be prepared for cold weather. While most days are sunny, continue to carry good rain gear. Consider carrying rain pants or a rain kilt. On the flipside, you'll be at a high altitude, so sun exposure is also an issue–especially if it is reflecting off the snow.

Northbounders and southbounders find the higher elevation of Colorado can mess with their otherwise trail-fit body. Be sure to hydrate, know the signs of altitude sickness, and take electrolytes. Higher altitude also means increased sun sensitivity and colder temperatures, so be sure to have sun protection (especially sunglasses) and extra layers.

Consider picking up a $3 Colorado Fishing license before entering the state. It contributes to the Search and Rescue Fund in the unlikely event you need to be rescued.

Northbound

Northbound hikers will likely experience hundreds of miles of snow in the San Juans. Carry an ice ax and microspikes. Many hikers even carry snowshoes and, occasionally, skis.

Consider waterproof lightweight hiking boots and waterproof socks to keep your feet from going numb from day after day of walking in snow.

You may need to sleep on snow, so consider a more insulated sleeping pad with a higher R-value. You may also need to melt snow for drinking water, so pick up a backpacking stove and cook pot if you were stoveless in New Mexico.

We hiked with an ultralight northbounder who struggled without an adequate sleeping pad or stove in the South San Juan and purchased both in the trail town of Pagosa Springs before entering the high San Juans—though, they could've had them sent from home if they had planned ahead.

Parkview mountain in northern Colorado is often snow-free by the time both north and southbound thru-hikers reach it. Photo by John Carr.

Even the hardiest ultralight thru-hiker will want their pack weight to go up in this section and it is worth it given the challenges of these high altitude mountains. Hikers will usually spend a zero-day (rest day) in the trail town of Chama, NM, to pick up gear at the post office that they mailed themselves at the post before entering the Southern San Juans. If you were traveling solo or a couple so far, plan to travel through this section with a larger group.

Colorado's slopes are notorious for spring avalanches. Before leaving for the CDT, take a snow navigation course, mountaineering class with ice ax instruction, avalanche safety course, and practice. Note that many of these classes are only available in the winter, so you'll need to start learning many months before your trip begins.

Read up on mountaineering skills. Similarly, snowmelt swollen rivers can also make fords difficult for northbounders. Many northbound thru-hikers opt for the Creede alternate route through the San Juans to avoid the most dangerous snowy slopes.

Late season northbounders may see wildflowers. Herman Gulch, in particular, is a section of the trail that’s famous for over 100 wildflowers, including Colorado Columbines, lupines, and paintbrush.

Treeline Review editor Liz Thomas in southern Colorado as a southbound thru-hiker. Fall color from aspens changing color is a highlight. Note that she’s wearing a hunter orange bandana on her hat. Were she to do it again, she’d wear a lot more hunter orange.

Southbound

Colorado is generally easier for southbound hikers because the trail is usually snow-free. It is notable for its fall color. Due to the popularity of elk hunting in Colorado, thru-hikers are more likely to see hunters on the trail or off-trail in the Colorado backcountry than in other states. As in Wyoming, be aware of hunting season and opt for hunter-orange clothing.

Southbound hikers will want to push hard to get through the San Juan Mountains before early October. After October, heavy snows can come and have put an end to many southbounders’s hikes. Additionally, hiking in October increases the chance that you may be stranded in the snow and may not be able to be rescued. If you were not already carrying a satellite messenger on your thru-hike, carry one with you through the San Juans.

Northbound and southbound CDT hikers are likely to encounter afternoon lighting storms in Colorado. Carry a rain jacket, consider rain pants, and always check the weather. Several hikers die each year in Colorado from lightning strikes (though none have been long-distance hikers...yet). If possible, plan your hiking day to avoid the highest elevations during the afternoon. Be prepared to drop off exposed ridges and get to lower elevations. Opt for lower alternate routes if the weather looks bad. Read up on lightning preparedness and consider taking a Wilderness First Aid or Wilderness First Responder course to prepare yourself for what to do should someone in your party be struck.

Treeline Review editor Liz Thomas and friends hike through the San Juan mountains as northbounder CDT thru-hikers. Photo by Whitney LaRuffa.

Special Gear for Colorado

Electrolytes to help with altitude

Extra insulating layers like a down jacket or synthetic jacket

Sun protection like a sun shirt, sunglasses, and sunscreen

Special Gear for Northbounders in Colorado

Backpacking stove and pot for melting snow into water (if you weren't already carrying a stove)

Special Gear for Southbounders in Colorado

Hunter orange hats and clothing

If late in the season: satellite messenger, ice axe, winter traction devices, snowshoes, waterproof socks, backpacking stove, and cooking pot.

A CDT hiker in the Wind River Range at an alpine lake. Photo by John Carr.

Wyoming

Distance: 508 miles (815 kilometers)

Elevation Gain: 60,000' (18,000 meters)

Elevation Loss: 61,000' (19,000 meters)

High Point: Lester Pass (11,116 feet or 3,388 meters)

Low Point: North of Rawlins (6,522 feet or 1,988 meters)

Though it has the fewest CDT miles, many thru-hikers find Wyoming one of the most memorable states. Home to the Wind River Range mountains, Yellowstone National Park, and the Great Basin, Wyoming has many of the highlights of the CDT. These regions are diverse, from hot and windy desert to high alpine mountains–so you'll want to carry versatile gear through this state.

A CDT thru-hiker in Yellowstone National Park next to a hot spring geyser. Photo by John Carr.

A week before reaching Yellowstone, whether northbound or southbound, make sure you have permits secured for backcountry camping in the Park. See our section on how thru-hikers get permits for Yellowstone. As an alternate, some thru-hikers choose to go through Grand Teton National Park.

For northbounders, Wyoming is the first state you'll reach where grizzly bears live. We strongly recommend picking up a lightweight Ursack bear resistant bag or bear canister before entering the Wind River Range.

We also recommend storing any food, trash, or toiletries in an odor-proof food bag before putting them in the bear canister or Ursack at night.

From the Wind River Range to the Canadian border, most thru-hikers carry bear spray. Before leaving for the CDT, we recommend practicing using bear spray with an inert canister. Be bear aware and read up on keeping yourself safe in grizzly bear country.

Most thru-hikers find the Great Basin to be easy walking. It's a relatively flat section of the CDT, mostly on rarely-trafficked dirt roads. As one of the lower elevation parts of the CDT, many thru-hikers will jump to the Basin if the snow in Colorado is too high and will flip flop back to the San Juan mountains in Colorado after the snow has melted.

The Great Basin is home to wild horses, whose poop towers are found nowhere else on the CDT. Although the distance is long between water sources, most thru-hikers find they can up their mileage. There are almost no trees in the Basin, so you won't have much shade or protection from the abundant wind in this area. We recommend ample sun protection, including a sun umbrella (which can also help block the wind). Six Moon Designs, Gossamer Gear, Hyperlite Mountain Gear, and Montbell are all brands that offer mylar windproof umbrellas designed for sun. As with New Mexico, bring extra water carrying capacity.

The Wind River Range (aka "the Winds") is considered one of the most beautiful parts of the CDT. These high, rugged mountains are beautiful for northbound and southbound hikers. Most northbounders will reach the Winds after most of the snow has melted and will encounter incredible wildflower displays and mosquitoes. As in Colorado, it can snow in any month in the Winds. Especially if you are opting for one of the popular off-trail alternate routes through the Winds, carry a satellite messenger.

Special Gear for Wyoming

Special Gear for Northbounders in Wyoming

Treeline Review editor Liz Thomas in the Deerhead Salmon National Forest in Montana on the CDT.

Montana and Idaho

Distance: 972 miles (1,564 kilometers)

Elevation Gain: 173,000' (52,000 meters)

Elevation Loss: 177,000' (54,000 meters)

High Point: Elk Mountain (10,094 feet or 3,077 meters)

Low Point: US — Canadian border (4,215 feet or 1,285 meters)

Montana/Idaho is likely the state that has the biggest differences between the northbound and southbound experience. Southbounders will start in a snow-covered Glacier National Park and will likely require an ice ax and winter traction devices (see above for information about the termini). Northbounders may get colder temperatures and a dusting of snow but will generally not have to deal with the snowpack and snowmelt seen by southbounders.

Most southbounders find Montana hot, especially after leaving Glacier National Park. The trail may be harder to follow, and the brush along the trail may be thicker. Distances between water sources can be an issue, especially in the heat. Have extra water carrying capacity, use sun protection, and take electrolytes.

Glacier National Park as seen by southbound hikers in June.

Northbound hikers will find Montana to be cooler and will feel the pressure of the weather to finish before the big snow hits. As the weather turns, be sure to carry quality rain gear and consider rain pants. Some water sources may be dried up, so try to carry extra water carrying capacity. Depending on your timing as a northbounder, be cautious of when hunting season opens and consider wearing hunter orange clothing.

Both northbound and southbound thru-hikers will be traveling in grizzly country. As with Wyoming, carry bear spray and a way to protect your food, make noise to prevent startling a grizzly, and read up and practice what to do if you encounter a grizzly bear.

Whether northbound or southbound, you'll need to secure permits secured for Glacier National Park and the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. See our section on how thru-hikers get permits.

Special Gear for Montana/Idaho

Special Gear for Northbounders in Montana/Idaho

Extra insulating layers like a down jacket or synthetic jacket

Hunter orange clothing

Pie Town, New Mexico is one of the trail town highlights for many CDT thru-hikers. Photo by John Carr.

CDT Resupply Strategy

Ask ten thru-hikers about their resupply strategy, and you'll get ten different answers! Resupply strategy depends on so many factors. How picky are you? Can you resupply from a Dollar General, or do you want a Whole Foods? Do you like extra-long hitches into towns for resupply, or would you rather grab your box and keep going? Do you have dietary restrictions (celiac, vegan, allergies)? What's your food budget? Does it take time for your hiker hunger to arise?

Some hikers refuse to send resupply boxes (and can resupply with ketchup packets and ramen), while others rely entirely on boxes. Most hikers are somewhere in the middle.

For this discussion, we'll give you some broad, sweeping generalizations about resupply strategy for the CDT. If you have thru-hiked another long trail before the CDT, your resupply strategy will also work for the CDT. If you're a first-timer, it will take some time to figure out what works best for you.

There are some locations on the CDT where sending a resupply box will make your life a lot easier. We recommend sending boxes to the following locations (south to north):

Doc Campbell's, NM (or you can pre-order any food/supplies you will need)

Pie Town, NM

Encampment, WY

South Pass City, WY

Leadore, MT (this is borderline)

Lima, MT

Benchmark Wilderness Ranch, MT

Additionally, many hikers choose to "bounce" specialized gear items ahead. For example, if you are southbound, you may enjoy having a stove for the cold and snowy Glacier National Park section and not need it for a few months until you're back in the cold San Juan mountains in Colorado. For northbounders, you may want to bounce extra water-carrying capacity ahead to the Great Basin. Use the Post Office General Delivery service to avoid carrying gear until you will need that item.

Dealing with Hiker Hunger on the CDT

Treeline Review writer Mike Unger in Lake City, Colorado.

“Hiker hunger” eventually kicks in for most thru-hikers on a long trail. Hiker hunger is the insatiable hunger that happens when your body can't keep up with the chronic calorie deprivation that is a thru-hike. It may take a few weeks for hiker hunger to kick in for some people. Sometimes, the opposite occurs in the first part of a thru-hike — we’ve known some hikers who lose their appetite when nothing tastes good. When this happens, your energy levels and motivation both take a hit.

Through the years, we've developed some strategies that have helped us manage hiker hunger:

Understand that your taste buds may change. Altitude, desert heat, and fatigue may make foods that you think you will want on the trail unpalatable when you’re actually on the trail. So while you’re hiking, listen to what your body craves, make a note, and buy it at your next town stop.

Because your taste buds may change, we usually don't recommend relying exclusively on resupply boxes as a strategy for most thru-hikers (except at a very few towns that otherwise don't have robust resupply options — see our list in the resupply section). The expenses of shipping resupply boxes add up, especially if you don't like the food you mailed yourself and have to buy all new food.

If hiking food isn’t cutting it for you, stretch out that town stop as long as possible by carrying out town food. We’ve been known to carry out an entire large pizza or sandwiches (with condiments on the side). If your motel room has a kitchenette, use up an entire loaf of bread by making grilled cheese sandwiches and carrying them out. Some produce, such as carrots, avocados, and apples, will hold up well in your pack if you pack them carefully and eat them within a couple of days. Hit the bakery — scones and muffins also hold up reasonably well.

If you've lost your appetite, you should eat even if you're not hungry. Take regular meal and snack breaks. Tell yourself that food is fuel and your body needs it.

Embrace high-calorie foods that you may usually avoid in "real life." Fat is your friend. Most hikers seek out high-calorie foods (120 calories per ounce or more). Eat almond butter or Nutella right out of the jar.

For instance, it may be easier to drink than chew in certain scenarios, such as extreme heat or high altitude. You may consider drinking high-calorie or high protein drinks or carrying vitamins to supplement your diet and recovery.

how to stay Hydrated on the CDT

CDT thru-hikers collecting water from puddles in New Mexico on a section where water is very limited. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Hydration is a serious business on the CDT. You will have multiple 20+ mile water carries in New Mexico and Wyoming. You can’t rely on water caches.

Before filling your bottles, fully hydrate at every water source (known as “cameling up”). Then, as you fill up bottles, make sure you pack out enough water to reach the next guaranteed water source safely. The FarOut app makes it easy to know how far it is to the next water source, and user notes keep the information current. For that reason alone, we recommend getting the FarOut app.

The following are several other recommendations to stay well hydrated.

Drink on a Regular Schedule

Naomi claims she lacks the “thirst” gene and rarely gets thirsty. By the time she gets thirsty, it's usually a bad situation. Therefore, she has to force herself to drink on a regular schedule. Mike set an alarm on his watch to remind himself to drink every hour.

Women & Hydration

We have known some women hikers who deliberately do not drink as much as they should because urinating can be a chore (Naomi fully admits to this). Learn how to urinate efficiently and practice before you hit the trail:

Learn how to urinate with your pack on if you're wearing pants.

Learn how to urinate standing up if you’re wearing shorts or a skirt.

Use a “pee rag,” which is much more convenient than TP. We like the antimicrobial Kula Cloth. We recommend getting a retractable lanyard so you don’t have to take off your pack to access your pee cloth.

Use Electrolytes

Electrolytes are essential in New Mexico and the Great Basin — and a good idea for the entire hike. Water alone is not enough when exerting yourself in hot and exposed conditions.

During Mike and Naomi’s PCT Nobo hike, they came upon a hiker sitting in the shade with his head in his hands, unable to continue hiking. He didn’t understand what was wrong because he drank lots of water. They asked if he used electrolytes, and he hadn’t. He was possibly headed toward hyponatremia. So they gave him a packet of electrolytes, and it was like someone had turned on a light switch. He immediately came back to life and was able to continue hiking. Lesson learned: electrolytes matter.

The good news is that electrolytes are easy to find and come in many forms. Powder drink mixes, liquid drops, flavored dissolving tablets, or capsules — flavored or unflavored — are all readily available. Pick the form you are most likely to use and use them regularly in New Mexico. Salty snacks are also good — in fact, you’ll likely find that you crave salty over sugary foods. That’s your body telling you what it needs. Listen to it and feed it accordingly.

Read our in-depth review of electrolytes written by a nutritionist-turned-thru-hiker, where we discuss the pros and cons of each type of electrolytes, when to take them, and more.

Drink Mixes & Electrolytes

You will drink a lot of warm, poor-tasting water in New Mexico and the Great Basin. We find it extremely helpful to carry a drink mix to improve the taste of water. Mike and Naomi’s favorite non-electrolyte drink mix is the True Lemon line of mixes. They are low in sugar and taste great.

Pro tip: Keep a separate, dedicated water bottle for drink mixes to prevent contamination confusion. We like the wide-mouthed Vitamin Water bottles for our drink mixes.

Use Good Water Containers and Carry Extra Water Capacity

Mike and Naomi started using the Cnoc Outdoors Vecto water containers in 2018 for a hike of the Grand Enchantment Trail — a rough desert and mountain route between Phoenix and Albuquerque. They have also used the Cnoc bags on the Arizona Trail, Great Divide Trail, Idaho Centennial Trail, Blue Mountains Trail, Oregon Desert Trail, and PCT. They find the Cnoc bags more durable than Platypus bladders or Sawyer water bags. Their 2-liter Cnoc Vectos have been dropped, squeezed, and carried through thorny brush. They've only had one fail in all of those trail miles. They can’t say the same for Platypus or Sawyer bags.

DIY Gravity Filter

Mike and Naomi like to use the Cnoc Vectos as a gravity system with the Sawyer Squeeze filter.

You use a Sawyer coupler to attach two Cnoc Vecto bags to a filter. You can filter two liters in less than five minutes — all hands-free without any squeezing. They also recommend using Nite Ize gear ties to hang the Cnoc/Sawyer gravity system.

Treeline editor-in-chief Liz Thomas likes to use her Sawyer Squeeze as an inline filter. Using a Platypus Big Zip EVO Reservoir, she cuts the hose and inserts the Sawyer Squeeze using the Fast Fill Adapter. She fills the Platypus with dirty water and sucks on the bite valve of the Hoser; the water travels through the filter, and voila! Clean water.

Learn Thru-Hiking Skills

We have an excellent series on thru hiking skills:

How Not to Die on a Thru-Hike: Safety tips for first-time thru hikers and long-distance hikers, backpackers new to distance hiking, and experienced thru-hikers tackling a new kind of trail.

How to Train for a Thru-Hike: Everything you need to know in order to physically and mentally prepare your body and self for a long-distance hike…and why training matters.

How to Thru-Hike as an LGBTQIA+ Person: Six LGBTQIA+ thru-hikers share advice on motivation, safety, and being queer outdoors to get you inspired to backpack a long trail.

How to Thru-Hike Over 60 Years Old: Five thru-hikers age 60+ share advice on gear, training, nutrition, injury, recovery and motivation.

Snow Skills for Thru-Hikers: Tips for navigating the snow in Colorado’s San Juan mountains.

Thru-hiking Food: What I Eat on a Long Trail: Four thru-hikers share what they eat on a backpacking trail. Meal planning, resupply, dehydrated recipes, stoves and cold soaking for omni, vegetarian, and vegans.

A Thru-Hikers Guide to Hitchhiking: Learn how to hitchhike with 42 tips from thru hikers.

How to Ford a River: Safety tips for crossing rivers and creeks while thru hiking.

How to Take Care of Your Feet on a Thru-Hike: Our best tips on preventative foot care.

Thru-Hiking Risk Assessment and Decision Making: Risk assessment and decision making tips and advice for thru hikers in a high snow year.

Thru-Hiking in a Big Snow Year: Thru hikers share their safety and gear tips for hiking in big snow years.

How to Pack a Backpacking Backpack: Balance weight and maximize comfort.

How to Choose a Backpacking Backpack: How to fit and find the best pack for you.

How to Support a Thru-Hiker: Read this and share it with the person who will be supporting your thru hike.

How to Maintain Fitness After a Thru-Hike: Be ready for your next adventure and maintain that fitness!

Bears on the CDT

Bears are present in nearly every section of the CDT. However, grizzly bears are only in Montana and mostly in Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. We recommend carrying bear spray from South Pass City to the Canadian border. Get a holster for easy access (it won't do you much good if it's inside your pack). Learn how to react if you encounter grizzly bears. Seriously — read this multiple times so that your reaction will be automatic.

Bears are rarely aggressive, but they are opportunistic. Never leave your pack unattended (even when you are relieving yourself), keep a clean campsite, and consider cooking a few miles before you stop and camp. Carry bear canisters when required and consider odor proof food bags and even Ursack bearproof bags in areas of known bear or critter activity. See REI’s guide to Backpacking in Bear Country and Food Storage and Handling in Bear Country for more information.

Cows and Cow-Water on the CDT

A CDT thru-hiker filling up their water from a windmill-fed cattle trough. Cows will be a consistent theme for your CDT thru-hike. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Public land all along the CDT is used for grazing cattle or sheep. Many of your water sources from New Mexico to Montana (the entire trail) will be shared with cows. Sometimes, cows will use your water tank as a bathroom. For hikers who have been on the Arizona Trail or Oregon Desert Trail, similar methods for dealing with cows will apply.

We highly recommend carrying a good water filter on the CDT and back-flushing it regularly (or replacing its filter regularly, depending on its design). See our Best Water Filters and Purifiers for Backpacking guide for our recommendations.

Additionally, we recommend pre-filtering many water sources with visible floaties. As a southbound thru-hiker, I once drank from a cow tank where the water was as brown as chocolate milk. Many thru-hikers will treat the worst water sources a second time with chemicals and then add an electrolyte or flavored drink mix to cover the taste.

Cows will often go to the bathroom in the shade of that one tree you may want to use for a break or windbreak on your campsite. At some point in your hike, most thru-hikers find the need to kick dried cow patties out from a campsite or rest stop.

Lastly, cows may be territorial or aggressive on the CDT. Longhorn cattle in the Great Basin of Wyoming can be intimidating. Look big, keep your distance, and be assertive.

The view from the tent in the Wind River Range. Certain sections of the CDT may have many mosquitoes during certain months, so plan to have a good bug net on your tent. Photo courtesy John Carr.

how to deal with Mosquitoes on the CDT

Most thru-hikers will encounter mosquitoes on the CDT. Where you see them depends on your direction (northbound or southbound) and when you start. If you're hiking southbound, you'll likely see them in the southern part of Glacier National Park, the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and the Wind River Range. Northbounders will see them in Colorado and the Wind River Range. We recommend carrying a mosquito head net for those sections and some good bug spray. If you're wearing a skirt or shorts, you may also want to consider some lightweight wind pants — especially if you don't like putting bug spray directly on your skin.

CDT thru-hikers taking phone photos of each in the Gila River in New Mexico. Note how both have a good waterproof phone case to protect their phone. Photo by John Carr.

Waterproof and Charge Your Electronics

Many hikers use their phones to take photos, stay in touch with folks back home, and navigate. Rain and trail dust is tough on cameras and phones. Always carry paper maps as a backup on the CDT. The CDT is remote, and getting lost is common. We also recommend getting yourself a good phone case and considering a separate dedicated camera, ideally a rugged, waterproof, freezeproof, dustproof camera. Keep your electronics in your sleeping bag at night to keep your batteries from freezing, or use a Phoozy thermal phone case. Your phone battery is unlikely to last days between trail towns, so most hikers carry an external battery and cords needed to keep their devices charged on the trail.

How to Manage Your Money

Lander, Wyoming is one of several trail towns that allow hikers and cyclists to camp in the public park. Camping while in town is a way to still have access to the amenities of town without paying for a hotel. Ask locals if there is a free place you can camp legally while in town. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Running out of money is one of the most common reasons people end their CDT thru-hike.

Choose gear well the first time

Choose your gear well the first time, and you won’t have to spend your limited thru-hiking dollars on replacing damaged gear or switching out gear that didn’t work for you. In particular, find a backpack that fits you and your gear well.

It’s very common for thru-hikers to purchase several packs throughout their first thru-hike as they search for the best one. Common backpacks on the CDT are the Gossamer Gear Mariposa and ULA Catalyst and Hyperlite Mountain Gear Southwest, all of which are the higher volume packs made by ultralight manufacturers.

While all these packs are rated to 35 pounds, we recommend keeping your base weight less than 15 pounds to comfortably carry the amount of food to cross the remote sections of trail. See our Best Lightweight Backpacking Backpacks gear review for ones that consistently work on different trails.

Limit town stays

Many Triple Crown thru-hikers think towns on the CDT are the most expensive out of the three. This fact is especially the case for resort towns in Colorado. Limiting your town stays (especially on zero days) is the easiest way to preserve your funds. However, the CDT is cold and physically taxing. While planning, no matter your best intentions, you will want some hotels during this thru-hike. Most thru-hikers find they need more rest on this trail than any other.

How to save money while on a zero day

We know one CDT hiker who eats a can of beans when he enters a town to help reduce his restaurant spending. Limiting alcohol and eating from grocery stores instead of restaurants can help quite a bit. Split hotel rooms with others, but check with the hotel to make sure that is okay first.

Reduce off trail expenses

Get your off-trail expenses (e.g., cell phone, storage unit) to an absolute minimum. If you own a car, park it in a storage unit and tell your insurance company that you'll need only minimal insurance for five months. Cancel all recurring expenses you won't be using (cable TV, internet, etc.)

Protect Your Feet

At one time or another, most CDT hikers experience foot issues such as blisters, damaged toenails, or strained ligaments. When Treeline editor Liz Thomas worked the CDTC shuttle at the southern terminus in New Mexico, she would regularly rescue hikers whose blisters were too bad to continue.

Air out your feet during breaks, soak your feet whenever possible, change your socks regularly, and immediately address all issues (hot spots, rocks in shoes, etc.). Most hikers find that using a trail runner instead of a hiking boot allows their feet to dry out better to reduce the number of blisters in the desert. Trail running shoes like the Altra Lone Peak or Brooks Cascadia are the most common shoes for thru-hikers. See our Best Trail Running Shoes gear review for more recommendations.

Related: How to Take Care of Your Feet When Hiking and Backpacking

Read More: The Best Hiking Socks

Treeline Review photographer John Carr hitch hiking on the CDT. Photo courtesy John Carr.

Hitchhiking

It's inevitable — there will be times when you need to hitchhike to get into town on the CDT. For many hikers, it's their least favorite aspect of thru-hiking. We've heard horror stories from all genders, so it makes sense for everyone to take precautions and be prepared. Here are some things we've learned about hitchhiking as a thru-hiker:

Before you stick your thumb out, put your phone and your wallet somewhere on your person, hopefully in a zippered pocket. If you have to bail, you’ll still have some way to call for help and access to money.

Before you stick your thumb out, organize your gear. Fold up your trekking poles and secure them outside your pack, secure your water bottles, etc.

If you have a relatively clean sleep shirt, put it on so that you don't stink up the entire car.

Choose your spot carefully. If possible, stand in a place where there is room for a car to pull onto the shoulder safely.

Before you get in the car, discretely take a photo of the license plate with your phone or camera if possible.

If you don't get a good vibe from the driver, do NOT get in the car. Trust your instincts. Make up a reason for why it won't work.

If you smell alcohol, do NOT get in the car.

Smile and look friendly!

If you're part of a big group, try splitting up. Cars won't stop if they think you all won't fit.

In extremely remote areas, you may have to consider a multi-part hitch.

Half of the CDT in Rocky Mountain National Park was damaged during the East Troublesome Fire in October of 2021. As a result, the trail is closed. Photo courtesy John Carr.

What to do About Wildfires on the CDT

Wildfires are an annual occurrence on the CDT, especially in a low snow year like the Rocky Mountains saw in 2022. Always check for trail closures before heading into a new section of trail. The Continental Divide Trail Coalition website is updated almost daily as conditions change. Apps like FarOut will also have updates, often in the user-submitted comments section but if you use Gaia GPS, that is not always something you can see with every subscription level.

If you see smoke or suspect a fire, check to see if there is a fire nearby and make a safe decision accordingly. Read the CDTC's website for how to report fires, react to nearby fires, shelter from fires, and assess the danger of a nearby wildfire.

The Gaia GPS app has a current wildfire map layer.

What to do About Trail Closures on the CDT

Sections of trail are often closed even after a wildfire is extinguished. These fire closures typically last a few years to give the forest soil some time to re-stabilize and give trail builders time to remove downed trees.

Trail closures and adapting to them are part of the CDT experience. As with all trail skills, the more you know before you go, the better you will be able to be flexible as closures come up.

In many cases, the CDTC website will list alternative trails that you can take to keep your footsteps connected (i.e., not have to hitchhike around a fire closure). In some cases, an alternative trail does not exist, and you will have to take a bus or get a ride and skip the closed section.

Check the website before you start your thru-hike to develop a plan to get around areas that you know will stay closed during your thru-hike. Before entering a new section of trail, check the website to ensure that you are not about to enter a recently closed area.

Leave No Trace

Portions of the CDT are shared with other users, including vehicles and bikes. Being aware of other users and yielding to horses are part of the ethics of being outdoors. Photo courtesy John Carr.

The CDT is an amazing route because it is so remote and seemingly untouched by humans. Yet as more thru-hikers hike the CDT, the greater the potential for impact. Leave No Trace (also known as LNT) is composed of seven ethics for the backcountry. LNT acknowledges that we humans are a guest in the outdoors, and we seek to leave the PCT in better shape than we found it. The goal of LNT is to create an outdoors that will be as beautiful for future generations as it is now. See Leave No Trace’s website for more on the seven principles.

Several gear hacks can make LNT a breeze when it comes to CDT thru-hiking.

Use a Potty Trowel

LNT requires you to bury human waste 6-8” deep. We recommend carrying an ultralight backcountry potty trowel (bonus: it doubles as a stake). Potty trowels dig deep through rocky and rooty soil much better than using a rock or your shoe. Bonus: you can use the trowel as a tent stake in the snow or to dig out a snowed-in campsite.

pack out used toilet paper

It’s become standard for thru-hikers to pack out their used toilet paper (for a few years, it was getting pretty gross along the trail corridor).

The easiest way to do this is by including doggie waste bags in the bag where you keep your toilet paper and potty trowel. Treat your used toilet paper like you would picking up dog waste in a park. Tie off the bag and put it in your trash bag. Easy, simple, and clean.

Read More: Essential Backpacking Accessories

Should I Have a Campfire on the CDT?

Most CDT thru-hikers find they don’t have time, energy, or interest in campfires. They’re not very popular among thru-hikers these days. Additionally, many high alpine areas don't have wood for burning. Lastly, with drought and annual wildfires devastating the Rockies, many forests ban campfires everywhere.

On other trails, like the PCT, thru-hikers have started campfires that got out of control and burned significant parts of the trail while also putting firefighters and local towns in danger. That's yet another reason the CDTC recommends not having a campfire on the CDT.

With that being said, while it isn't an everyday affair, most CDT hikers have at least one campfire during their six-month thru-hike. The difficulty of the CDT can reduce morale, and a campfire can help. Additionally, in very cold or wet conditions, CDT thru-hikers may find having a fire can restore warmth and dry gear in what feels like a life-or-death situation. If you have a fire, make sure you have enough water to put it out completely. Remember to drown it, stir it, and feel to make sure it is out cold before leaving the area.

Alternatives to a campfire while backpacking the CDT

If you want warm food and the comfort of a fire, there’s a simple solution: carry a backpacking stove with a fuel canister. We recommend carrying a backpacking stove with a fuel canister rather than an alcohol stove or wood-burning stoves (both are banned in many parts of the trail now). As more trail towns along the CDT become CDT Gateway communities aware of hikers' needs, it's become much easier to find fuel canisters.

Why You Should Trust Us

Mike Unger is one of few people in the world to have thru-hiked the PCT end-to-end both as a northbounder and southbounder. He’s a double Triple Crowner, having completed the Pacific Crest Trail, Appalachian Trail, and Continental Divide Trail each twice (and he’s working on the third hike of each). You can see all articles by Mike Unger on his Treeline Review author page.

Liz Thomas has thru-hiked the PCT as a northbounder and completed the PCT a second time as a section-hiker over ten years. A former Fastest Known Time (FKT) record holder on the Appalachian Trail, she has also hiked the PCT and CDT and is a Triple Crowner. She’s co-founder and editor in chief of Treeline Review. You can read all her gear articles here and on her personal website, as well as on Wikipedia.

Naomi Hudetz has thru-hiked the PCT, CDT, and AT and is a Triple Crowner. She’s co-founder and online editor at Treeline Review. She’s thru-hiked numerous other distance routes including the Great Divide Trail across the Canadian Rockies (twice), Grand Enchantment Trail, Pacific Northwest Trail, the Arizona Trail, (most of) the Idaho Centennial Trail, the first known thru-hike of the Blue Mountains Trail, and the Oregon Desert Trail. You can read all her articles on her Treeline Review author page.

Trail Resources

There are some fantastic thru hiking preparation books out there that we highly recommend:

Long Trails: Mastering the Art of the Thru-Hike by our very own Editor-in-Chief Liz Thomas (Amazon | Bookshop.org)

Ultralight Backpackin' Tips by Mike Clelland (Amazon | Bookshop.org)

Lighten Up! A Complete Handbook For Light And Ultralight Backpacking by Don Ladigin (Amazon | Bookshop.org)

Trail Tested: A Thru-Hiker's Guide to Ultralight Hiking and Backpacking by Justin Lichter (Amazon | Bookshop.org)

Ultralight Survival Kit by Justin Lichter (Amazon | Bookshop.org)